TL;DR

Continuous Deployment is the goal of becoming a high performance team, rather than just a method. The main obstacle to continuous deployment is the risk of deployment failures. We can measure the risk using confidence level and loss. Only when the risk is within the action area can the team implement continuous deployment. By increasing the confidence level and reducing the loss, we can control the risk within the action area.

Why does the team resist continuous deployment?

Our team has been progressing slowly in terms of continuous deployment. Although we have continuous integration, there is still a significant amount of manual operation involved in deploying all the environments. Moreover, before deploying to the production environment, the software must go through manual testing by the testing department. When we proposed continuous deployment, the initial reaction from the entire team was uneasiness, followed by questioning its feasibility.

At that time, I was puzzled by the team’s response. Why wasn’t everyone actively embracing such a good practice? How can we become a high performance team without continuous deployment? Why do we have to deploy dozens of story cards together? Why should we tolerate a 200-day lead time for changes?

Later, I realized that I had misunderstood the goals and methods. If every deployment by the team brings about many issues and even economic losses, even if we can establish a continuous deployment pipeline, the team would hesitate to let it run. After all, no one can bear the cost of losing one million for every code commit. Therefore, continuous deployment should not be seen as a method for improving team performance, but rather as the goal of improving team performance. To achieve continuous deployment, the first step is to reduce the risk of deployment failures and eliminate the team’s anxiety.

Risk is typically composed of three elements:

\[Risk = (A,C,P)\]- \(A\) is an event or situation

- \(C\) is the consequence of \(A\)

- \(P\) is the uncertainty about \(A\) and \(C\)

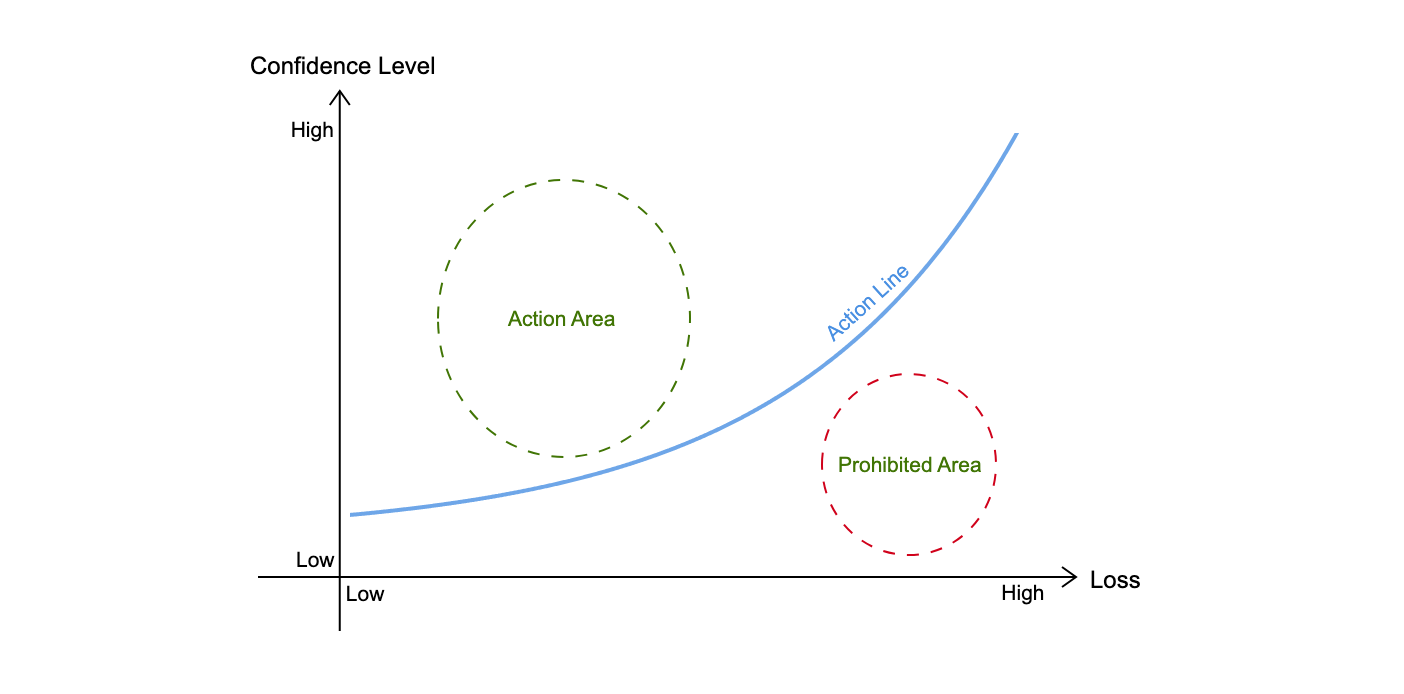

In this article, \(A\) represents deployment failure. So, we can use \(P\) and \(C\) to measure the risk of deployment failure. \(P\) represents the team’s confidence level in successful deployment (note that, \(the\ confidence\ level\ in\ successful\ deployment = 1 - the\ confidence\ level\ in\ deployment\ failure\)), and \(C\) represents the losses caused by deployment failure. To better illustrate the relationship between them, we can refer to the Fogg Behavior Model and create the following diagram.

From the diagram, we can observe the following:

- Only when above the action line, the team can potentially take action. Note that whether the action will be taken also depends on other objective conditions, such as the magnitude of the benefits, legal/company regulations, etc.

- The higher the loss, the higher the confidence level required for the team to cross the action line.

- The lower the loss, the lower the confidence level required for the team to cross the action line.

We can reduce the risk of deployment failure by increasing the confidence level and reducing losses, thus enabling the team to enter the action area. At this point, the team is prepared to implement continuous deployment, and we only need to provide necessary prompts and guidance. However, we cannot determine whether the team has already entered the action area, we can only speculate the team’s position by continuously gathering their views on continuous deployment.

How to quantify the confidence level?

What is the definition of successful deployment?

Before quantifying the confidence level, we need to first define a successful deployment. Continuous deployment is the automatic release of code changes into the production environment. Based on the current team’s practices, without considering automation, the definition of a successful deployment for continuous deployment is as follows:

- The test environment can be successfully deployed according to the documentation without any temporary fixes.

- The test environment is free of bugs.

- The production environment can be successfully deployed according to the documentation without any temporary fixes.

- The production environment is free of bugs.

Please note that in this article, “bugs” refer to deviations from customer requirements, rather than software requirements, as there may be omissions or errors in the software requirements. Additionally, we require that the deployment and testing in all environments are problem-free. According to the definition of continuous deployment, these are all part of the automation process, and their failures can affect the team’s confidence level in automation.

Laplace’s Rule of Succession

We can use Laplace’s Rule of Succession to quantify the team’s confidence level in the successful deployment. It was previously used by Laplace to predict the probability of the sun rising tomorrow.

If \(X_1, \dots, X_n\) stands for \(n\) known deployments, where a value of 0 represents failure and 1 represents success, then when there are \(s\) successful deployments out of \(X_1, \dots, X_n\), the probability of the \((n+1)\)-th deployment \(X_{n+1}\) is:

\[P(X_{n+1} = 1|X_1 +\cdots+X_n=s)=\frac{s+1}{n+2}\]The probability mentioned here refers to subjective probability, which is what we refer to as the confidence level.

We do not use the following formula

\[P(X_{n+1} = 1|X_1 +\cdots+X_n=s)=\frac{s}{n}\]because

- The above formula cannot handle the situation where there is no deployment, as \(\frac{0}{0}\) is undefined.

- The above formula cannot handle the situation where all known deployments are successful. \(\frac{10}{10}\) does not mean the team believes that the next deployment will definitely be successful.

- The above formula cannot handle the situation where all known deployments have failed. \(\frac{0}{10}\) does not mean the team believes that the next deployment will definitely fail.

- When there are a large number of deployments, the results of the two formulas tend to be consistent. However, when the number of deployments is small, the Laplace’s rule of succession is more reasonable.

The impact of deployment on confidence level

The impact of the first deployment is most evident

Before any deployment, the team’s confidence level in the first deployment is

\[P(X_1 = 1) = \frac{0+1}{0+2} = 50\%\]This means that the team has no clear preference for the deployment outcome.

When the first deployment is successful, the team’s confidence level in the second deployment becomes

\[P(X_2 = 1|X_1=1) = \frac{1+1}{1+2} \approx 66.7\%\]When the first deployment fails, the team’s confidence level in the second deployment becomes

\[P(X_2 = 1|X_1=0) = \frac{0+1}{1+2} \approx 33.3\%\]It can be seen that through the first deployment, the team has developed a clear preference for the subsequent deployments.

Continuous successful deployments can quickly increase confidence level

If the team can successfully deploy three times in a row, the team’s confidence level in the fourth deployment is \(80\%\).

\[P(X_4 = 1|X_1+X_2+X_3=3) = \frac{3+1}{3+2} = 80\%\]To achieve a confidence level of over \(90\%\), the team needs to successfully deploy at least eight times in a row.

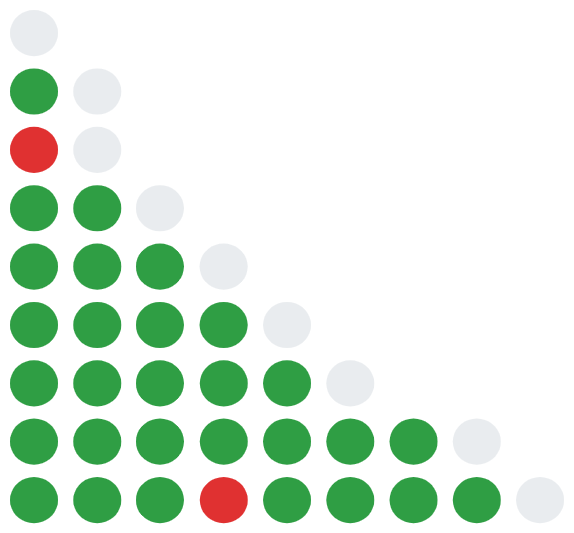

\[P(X_9 = 1|X_1+X_2+X_3+X_4+X_5+X_6+X_7+X_8=8) = \frac{8+1}{8+2} = 90\%\]We need more successful deployments to regain confidence level after a deployment failure

If the team fails on the fourth deployment, we would need four consecutive successful deployments in order for the confidence level to return to \(80\%\).

\[P(X_5 =1 |X_1+X_2+X_3+X_4=3) = \frac{3+1}{4+2} \approx 66.7\%\] \[P(X_6=1|X_1+X_2+X_3+X_4+X_5=4) = \frac{4+1}{5+2} \approx 71.4\%\] \[P(X_7=1|X_1+X_2+X_3+X_4+X_5+X_6=5) = \frac{5+1}{6+2} = 75\%\] \[P(X_8=1|X_1+X_2+X_3+X_4+X_5+X_6+X_7=6) = \frac{6+1}{7+2} \approx 77.8\%\] \[P(X_9=1|X_1+X_2+X_3+X_4+X_5+X_6+X_7+X_8=7) = \frac{7+1}{8+2} = 80\%\]How to improve confidence level?

From the analysis above, it is evident that in order to improve confidence level, we must ensure the success of deployment, which means that the deployed software meets the customer’s requirements. This is also the definition of quality in the book Quality is Free. In other words, improving confidence level is synonymous with improving the quality of deployment.

Improve the level of automation in environment deployment

Compared to other parts of the software development life cycle, environment deployment is often overlooked by teams due to its lower complexity, workload, and frequency. It frequently requires manual operations to be completed. These manual operations are prone to errors and easily identifiable. The team should prioritize the use of automated scripts to minimize them and reduce errors caused by environment deployment. For example, we can achieve one-click deployment for different environments.

Improve the quality of automated testing

We require both the testing environment and production environment to be bug-free during successful deployment. One of the key elements to ensure this is through automated testing. We define the quality of automated testing as its ability to quickly verify if the software can function according to the software requirements.

Based on the definition above, the types of automated testing and test cases should come from the software requirements, not the software code. From this perspective, test coverage and test quantity should not be used as metrics to measure the quality of automated testing. The correct measure should be the number of bugs identified after the software passes the automated testing. This requires us to focus more on how to design the types of automated testing and test cases based on the software requirements, which is known as the automated testing strategy. With an automated testing strategy in place, we can then set specific requirements for the team to improve the quality of automated testing.

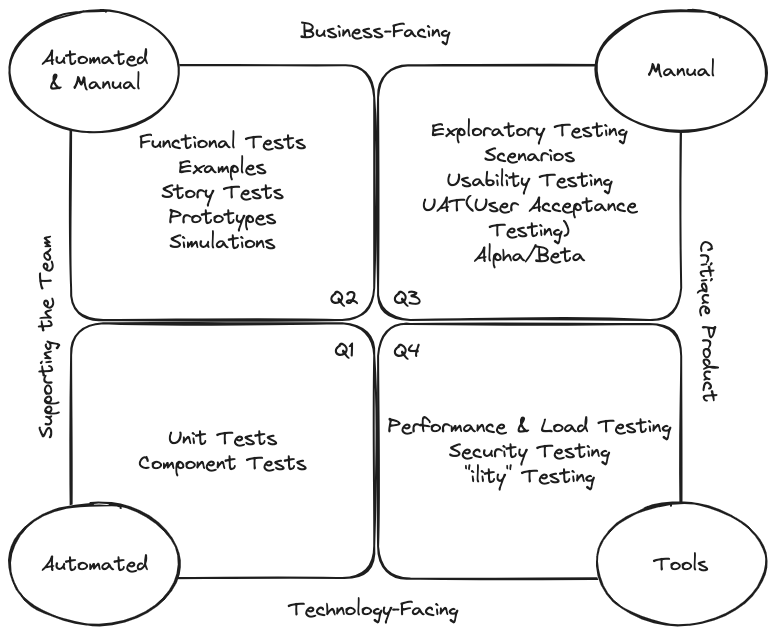

The diagram below shows the Agile Testing Quadrants from the book Agile Testing . It lists different types of testing and their applicable scenarios.

Using the most common types of tests as examples, such as unit tests, component tests, and functional tests, an automated testing strategy can require team members to implement functionality in the form of test-driven development, combined with the current architecture, and provide necessary test case examples and implementation steps. When a bug occurs, we can conduct a retrospective based on the testing strategy, the action could be requiring the team to adhere to the testing strategy or updating the testing strategy to ensure that the bug can be detected by automated testing. Conversely, the absence of an automated testing strategy would result in a lack of unified requirements for automated testing within the team, and the quality of automated testing would not be improved.

Automated testing should be fast, both in terms of execution speed and issue identification speed. For testing types that support team development, the execution time should be controlled within 5 minutes to avoid interrupting the team’s flow state and increase the number of test runs. Additionally, error messages from tests should be accurate to quickly locate problematic code. For example, we can require each test to have only one assertion and for test names to follow the given-when-then format.

Improve code quality

Our definition of code quality is that the code is able to function according to the software requirements. Team members serve as the bridge between software requirements and the code. In order to improve code quality, team members need to correctly understand the software requirements and have a proficient grasp of the basics of software development (language, frameworks, architecture, systems, etc.).

Correctly understanding software requirements

The process of understanding software requirements is a journey of acquiring knowledge, from known-unknown and unknown-unknown. It relies on the team members’ domain knowledge, the participants involved in the understanding process, and automated testing. The more domain knowledge team members have, the more participants are involved in this understanding process, and the higher the quality of automated testing, the more it contributes to team members correctly understanding software requirements.

We can try the following practices to deepen team members’ understanding of software requirements:

-

Share business context before the project starts. The context should include business background, business value, relevant stakeholders, communication channels, technical solutions, priorities, etc. This helps unify team members’ understanding of the project.

-

Conduct story card Kick Off with BA, QA, TL, and even PM participation. The team’s understanding of software requirements deepens over time, and the content of story cards may not reflect these changes in a timely manner. Therefore, we need to conduct Kick Off sessions before working on each story card to obtain the latest software requirements information. During the Kick Off, the BA may modify the requirements, QA may provide additional test cases, TL may optimize technical solutions, and PM may supplement any missing software requirements. The more diverse the participants, the deeper the team members’ understanding of software requirements.

-

Conduct a Desk Check with BA and QA participation. After implementing the software requirements, team members gain a deeper understanding at the code level, while BA and QA may gain a deeper understanding at the business level. The team can use Desk Check to realign the requirements.

-

Support running automated testing locally. Automated testing not only verify if the software meets the current requirements but also validate if the software still meets the existing requirements after code changes. Supporting the local execution of automated testing can help team members discover the relationship between current and existing requirements during development.

-

Pair programming. Pair programming allows two individuals to understand the same software requirement from different perspectives. This is especially beneficial in the expert-expert and expert-novice pairing modes for deepening the understanding of software requirements.

-

Provide timely feedback to BA during the development process. Team members’ understanding of requirements deepens during the development process. By analyzing the code implementation of existing requirements, we may discover many questions that the original requirements couldn’t answer. In such cases, it’s important to provide timely feedback and clarification to the BA to ensure the correctness and completeness of the requirements.

-

Adopt a lightweight approach to RFCs. RFC is a decision-making process that invites all relevant parties to review and provide feedback on proposals to ensure their reasonableness. Software requirements often involve many decision-making scenarios. By using RFC when the solution affects other teams, we can ensure that team members have a deep understanding of the upstream and downstream relationships of software requirements.

Proficient grasp of the basics of software development

The basics of software development determines the implementation of software requirements. It relies on the technical capabilities of team members as well as the knowledge accumulated by the team.

The best way to enhance the technical abilities of team members is through teaching by personal example and verbal instruction. I have conducted various trainings and workshops within the team, but the results were not particularly satisfactory. These methods can only impart knowledge but cannot effectively translate that knowledge into the skills of others. From my personal experience, the best training method is pair programming. It can be used to both impart knowledge and practice it. Verbal instruction can never convey as much information as personal example. Code Review is also a practical way to enhance technical skills. It allow team members to understand code from different perspectives, which is beneficial for both the breadth and depth of their skills.

The knowledge accumulated by the team is mainly reflected in the following documents:

- Onboarding document: This is the first document that every team member reads when they join the team. It includes environment setup, permission requests, business introductions, ways of working, commonly used resources, and more. Every new member should be able to start working within a week based on this document, and they are expected to update the document if they find any errors or omissions.

- Architecture Decision Records (ADR): During the implementation of software requirements, the team will have various discussions and decisions. These discussions and decisions are valuable assets of the team, and we can use ADRs to document them. This way, when new members join or when maintaining existing functionality, we can easily access the complete context.

- C4 model: C4 model allow team members to understand the current system from different levels, providing a foundation for them to start working.

Improve the quality of software requirements

The definition of software requirement quality is that software requirements can represent the customer’s requirements. When the software can run according to the software requirements but cannot meet the customer’s requirements, it indicates that there is a problem with the quality of the software requirements. True Professionalism attributes the primary cause of quality issues to poor communication with the customer. Customer requirements, like scientific truths, are difficult to attain. We can only approach them infinitely through conjecture and refutation. Even when customers directly tell us their requirements, they are often unreliable, as their requirements may change over time and in different environments. However, we can use various software requirement gathering methods to help us and the customers discover as many high-quality software requirements as possible, such as surveys, use case analysis, and prototyping. Regardless of the method used, the two main factors that affect the quality of software requirements are:

- Communication distance with the customer. The higher the frequency and depth of communication with the customer, the more likely we are to obtain high-quality software requirements.

- Verification cost of software requirements. During the software requirement gathering phase, we should strive to prove that the requirements are wrong rather than right. The lower the verification cost of software requirements, the higher the frequency of verification can be, increasing the likelihood of obtaining high-quality requirements. The worst-case scenario is to perform verification in a production environment. This type of verification can be proactive, such as A/B testing, or reactive, such as production incidents.

Continuous Improvement

Continuous deployment failures can quickly decrease confidence level. A crucial component of improving quality is addressing existing problems and preventing their recurrence. The retrospective is a vital practice for quality improvement that occurs at the end of each iteration. Its focus should not be on discussing team-building activities but rather on identifying the problems encountered during the current iteration and how to avoid them. PIR is a retrospective analysis of production incidents, typically involving major issues. It allows for a review of the timeline of the incident, analysis of the root causes, and discussion on measures to prevent the recurrence of such incidents.

How to quantify loss?

We quantify loss here using the failure costs, which refers to the expenses involved in dealing with issues after deployment failures. Please note that we do not consider prevention costs and appraisal costs because teams often do not consider activities such as retrospective, testing, and refactoring as risk factors.

\[\begin{align} Loss =& problem\ assessment\ time \times salary \\ & + problem\ resolution\ time \times salary \\ & + customer\ service\ time \times salary \\ & + customer\ compensation \\ & + implicit\ losses \end{align}\]- Problem assessment time: The time taken to identify the cause of the problem and provide a solution.

- Problem resolution time: The time taken to implement the solution.

- Customer service time: The time taken by customer service to handle customer complaints after the problem occurs.

- Customer compensation: Monetary compensation provided by the company to the customer.

- Implicit losses: Revenue that the company should have received but did not due to the problem, including income losses caused by customer dissatisfaction.

How to reduce loss?

Building an effective alert mechanism.

Alerting refers to the monitoring system being able to perform specified actions when it detects an issue, such as sending emails, making phone calls, or sending Slack messages, in order for the team to handle it promptly.

There should be alert strategies

Alerts should not be set up arbitrarily. We need to set alerts based on software requirements, just like automated testing strategies. Common types of alerts include system alerts, API alerts, performance alerts, and so on. We also need to set a reasonable escalation policy based on the severity of the problem to avoid manpower loss.

Alert should be timely

From the moment a problem occurs, every second counts and can potentially impact our customers. The longer the problem persists, the greater the losses. If we can receive alerts as soon as an issue arises, we can start addressing it immediately and minimize the impact. There are various mature alerting tools available in production environments, such as NewRelic, CloudWatch, AlertManager, etc. When setting up alerts, we need to carefully configure trigger rules to minimize detection time.

Alert should be accurate

Accurate alerts are essential to reduce problem assessment time. There are two aspects to consider: accurate alert trigger rules and accurate alert information. Incorrect trigger rules may result in undetected issues that should have been detected, or false positives that lead to revenue or manpower losses. Incorrect alert information can hinder our ability to quickly pinpoint the problem, thus increasing the time needed for problem assessment. For example, if the alert message indicates a problem with System B, but it is actually System A that is experiencing the issue, we would require additional assessment time to identify the problem with System A.

Building an effective disaster recovery plan

When a problem occurs, we need to restore the software to its normal state as quickly as possible to minimize losses. For simple issues, we can achieve software recovery through actions such as rolling back versions, disabling feature toggles, or switching traffic. However, complex problems often involve multiple systems and may require data recovery or message replay, making it impossible to achieve software recovery through simple operations. Therefore, we need a disaster recovery plan for each system, which should include various potential problems and their corresponding recovery solutions. It is also important to regularly practice and rehearse this plan to ensure that every team member knows how to respond in the event of a disaster.

When we anticipate that a deployment failure could lead to significant losses, we can adopt proactive deployment strategies to mitigate the risks. For example, we can use Canary Release and Blue-Green Deployment.

Improve the availability

For unstable third-party services, especially those that have encountered issues in a production environment, we need to decrease our confidence level in them and prevent potential problems in our architecture design, thereby minimizing the losses they may cause.

Firstly, we need to enhance the availability of our architecture based on the availability of the third-party services. For example, in response to the possibility of regional unavailability of the third-party service, our architecture needs to support multi-region disaster recovery. To address service unavailability caused by maintenance windows of the third-party service, our architecture needs to support data replay, allowing business continuity once the service is restored. To handle request rate limitations of the third-party service, our architecture needs to support peak load handling and caching mechanisms.

Secondly, we need to improve the availability of our architecture based on the reliability of the third-party service. For instance, for asynchronous messages from the third-party service, our architecture needs to support default actions after timeouts. For synchronous messages from the third-party service, our architecture needs to support conversion to asynchronous or message caching, enabling message replay in case of failures. In the event of synchronous call failures to the third-party service, our architecture needs to support synchronous or asynchronous retry mechanisms.

Summary

For continuous deployment, teams always have various concerns. If our metrics cannot reflect these concerns, it will be difficult to have a meaningful conversation with the team, and the implementation of continuous deployment may not proceed smoothly. Even if we enforce it through administrative orders, continuous deployment is likely to be stopped once policies, environments, or team dynamics change.

The risk metrics mentioned in this article are essential indicators. If we want to implement continuous deployment, these two metrics must be within the team’s action area. However, teams within the action area may not necessarily implement continuous deployment due to certain objective constraints, such as legal or company regulations that require written permission for deploying to production environments.

The correspondence between the risk metrics mentioned in this article and the DORA metrics can be summarized as follows:

- Confidence level corresponds to the change failure rate. The confidence level measures successful deployments, while the change failure rate focuses only on bugs in the production environment.

- Loss corresponds to the mean time to recovery. The time for problem assessment and problem resolution in the loss calculation and The time for problem detection adds up to the mean time to recovery. However, the mean time to recovery does not consider customer service time, customer compensation, and implicit losses.

Teams that have already measured the DORA metrics can also assess their readiness for implementing continuous deployment based on the change failure rate and mean time to recovery.

Comments