Recently I encountered a problem related to technical analysis. After the customer submits an order, they are unable to immediately view the latest order information. The team needs to conduct a technical analysis to find a solution. However, after conducting the analysis, the team only gave stakeholders one conclusion, which is that this problem cannot be solved, and the customer should wait to view the order later. My intuition tells me that there is a problem here.

From the team’s perspective, this is a normal answer, as there really is no feasible solution. However, from the stakeholders’ perspective, there may be many questions. Why can’t it be solved? Is the person responsible for the analysis not competent? Have they truly considered all possible solutions? Can I trust their conclusion? How should I explain this to the product team? It is evident that there is a serious information gap between the team and the stakeholders. The stakeholders can only accept this conclusion reluctantly or find someone else to redo the technical analysis, which mean this technical analysis is obviously be incompetent.

So, how can we conduct competent technical analysis? First, we need to know when it is necessary to conduct technical analysis. Then, during the process of conducting technical analysis, we must ensure that it meets the minimum standards. Finally, the results of the technical analysis should be outputted in the form of ADR and RFC.

When do we need to conduct technical analysis?

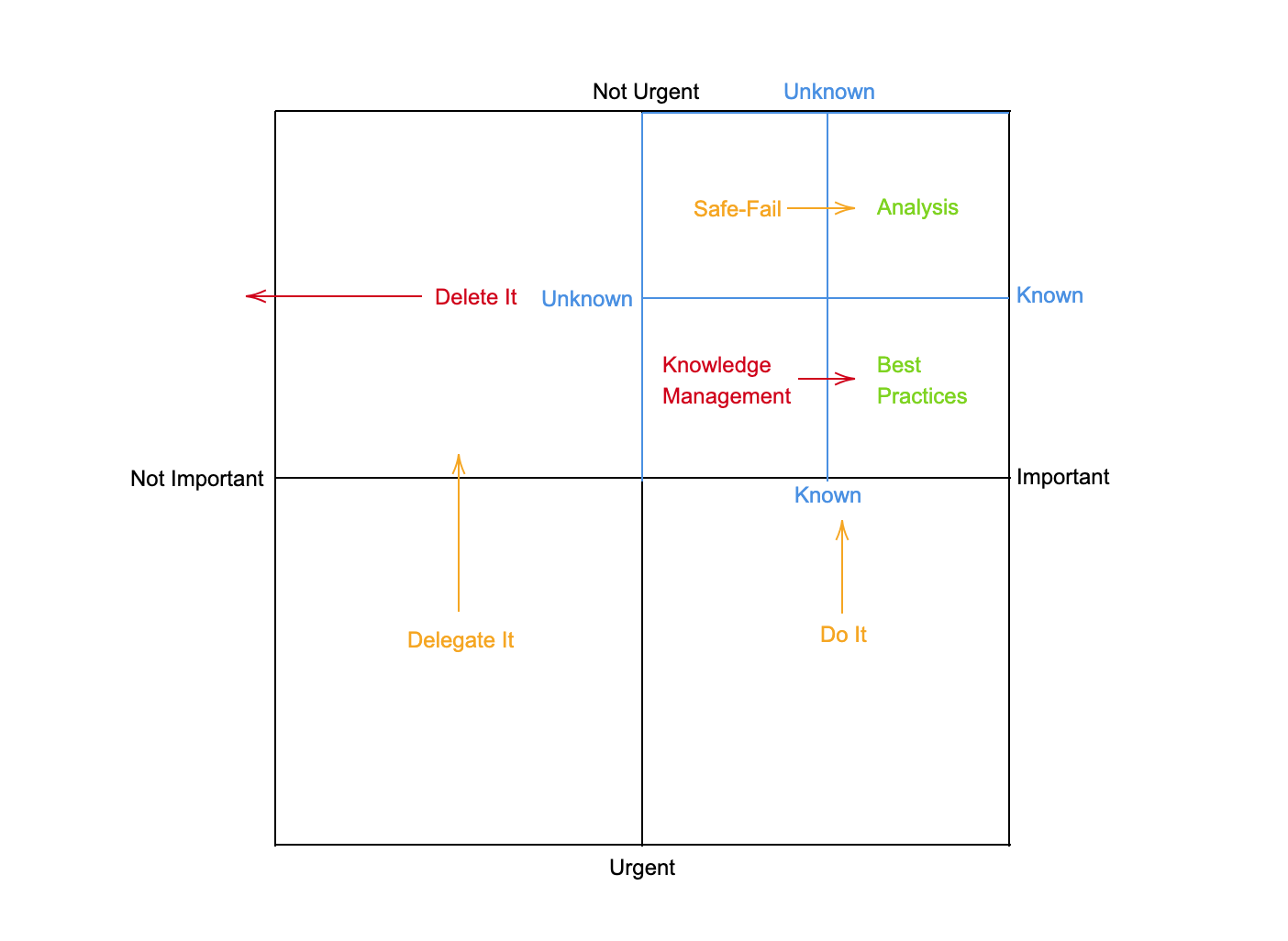

Technical analysis is used to solve complicated or complex problems, and not all problems require analysis. We can categorize problems from the perspectives of important-urgent matrix and known-known matrix. Different types of problems require different approaches for resolution.

Important - Not Urgent

From a time perspective, urgent problems usually do not give us time for detailed analysis. We need to take immediate action based on intuition and experience, but the main purpose of the action should not be to solve the problem, but rather to reduce its urgency and minimize the risk of making wrong decisions. For problems that are not important but urgent, we should delegate them fully and turn them into not-important and not-urgent problems. As for important and urgent problems, we should take immediate action in every possible way to gain more time for problem analysis, as it is difficult to guarantee that decisions made under stress are correct.

For problems that are not-important and not-urgent, we need to ask ourselves why we should solve them. These problems may be a waste of our time and should be avoided as much as possible.

Important but not-urgent problems should be the focus of our attention. Now, let’s further categorize them from the perspective of known-known matrix.

Known - Unknown

In terms of understanding, for problems that we have already understood or solved, we usually have a set of best practices to address them. In such cases, there is no need for analysis and discussion, such as Java syntax, variable naming, agile practices, and so on. However, if we have not managed the knowledge of solved problems at the team or individual level, such as summarizing, retrospective, knowledge sharing, etc., the same problems may recur, leading to unnecessary errors or losses.

For problems that we do not understand, if we know that someone in the team or industry understands it, then we need to analyze the problem and provide different solutions to support team discussions and decision-making.

If there are problems that we only become aware of after they occur and we cannot understand them, then we also need to perform analysis. However, the purpose of this analysis is not to solve the problem, but rather to minimize the losses caused by unknown problems, giving us an opportunity to learn from mistakes and define these unknown problems.

How to make a competent technical analysis?

Minimum standards

At least three solutions

Typically, a problem that needs to be analyzed should have at least two possible solutions.

-

Do nothing: Doing nothing means that although we are aware of the existence of this problem, considering factors such as cost, loss, and policies, we decide to take no action. This solution is often overlooked, but sometimes it can be the best choice. It can also remind us that the current problem may not be the right one to be addressed at the right time to the right people. For example, when the team’s manual testing efficiency is low, we propose solutions such as continuous deployment and automated testing. However, after several discussions, the team decides to do nothing because the current organizational structure does not support these solutions. This problem is not currently solvable and cannot be solved by a single team alone.

-

Disregard any constraints: Disregarding any constraints means that we can do anything we believe can solve the problem, and it will definitely be successful. For example, we can ask the team to have unlimited budgets, unlimited time, and unlimited human resources to solve the problem. This solution is often not adopted, but it provides enough space for imagination to guide us towards better solutions.

The above two solutions can be considered as the lower and upper limits of our problem-solving. Now, what we need to do is to find at least one solution between the lower and upper limits.

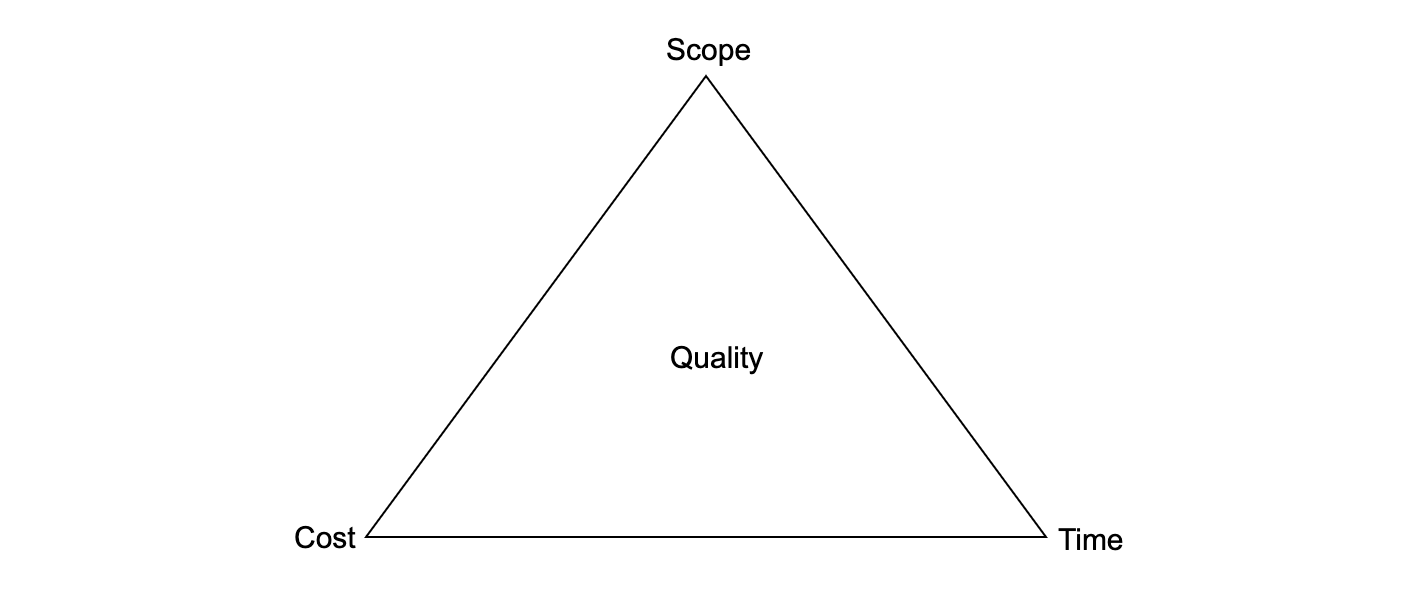

At least four evaluation dimensions

From a project management perspective, we can use at least three dimensions, namely time, cost, and scope, to evaluate each solution, as every stakeholder is concerned about when the solution can be completed, how many resources are required, and what modifications are included.

However, for technical analysis, we can further refine these dimensions to obtain more dimensions.

- Time: We can evaluate the solution from aspects such as short-term, long-term, and before or after certain important time milestones. For example, if we adopt a monolithic architecture, it can meet the requirements for rapid delivery in the short term, but the maintenance cost will increase significantly in the long term.

- Cost: We can evaluate the solution based on factors such as the difficulty of code implementation, the talent pool of the current team, and the degree of dependence on external or infrastructure. For example, if we adopt a monolithic architecture, the code implementation is simple, no need to expand the current team, and no additional AWS services are required.

- Scope: We can evaluate the solution based on business requirements and cross-functional requirements. For example, if we adopt an asynchronous processing solution, customers need to wait for 5 minutes after submitting an order to view the order details, which does not meet the immediate order viewing requirement. However, the system can automatically recover in the event of an error, ensuring higher stability.

After determining the evaluation dimensions, we need to apply them to all solutions. This way, we can have a unified understanding of all solutions, facilitating team discussions and decision-making.

Where to find solutions?

Problems that we don’t understand usually don’t have a unique solution. What we need to do is utilize all the knowledge we can gather to analyze the problem. During this process, we have three sources of knowledge:

-

Independent individuals: These are people other than ourselves. They can be other team members or experienced professionals from a third party, such as domain experts or consultants. The only requirement is that they provide independent opinions, so that we can avoid biases and noise as much as possible. For example, if someone in the team has absolute authority, it would be difficult to collect different solutions after they have given their own.

-

Different versions of ourselves in different scenarios: Imagine how we would solve the problem in different scenarios. Looking at the problem from different perspectives often leads to new discoveries. For example, consider what reasons could have led to the failure of solving the problem in the future. This method is also known as a pre-mortem .

-

Different versions of ourselves in different times: If we can’t come up with a solution, take a nap or engage in physical exercise, then revisit the problem the next day. Many innovative solutions come to us in moments of inspiration.

We should record all the possible solutions we can find, including those that we believe are impossible. If we don’t document certain solutions, they become exclusive information that we possess, which is not conducive to making the final decision because that information may provide important insights to others.

What should be output?

The ADR is a document used by teams to record architecture decisions. It includes the background, context, alternative solutions, decision outcomes, and the people involved in the decision-making process. While it is a document, the process of writing the document is a technical analysis process. If we include the process of requesting for others’ comments and the decision-making process, the whole process is called RFC. It can also be documented, such as the modification history of ADR, comments records, and decision meeting records. ADR and RFC can be used not only to solve architecture problems but also to solve other problems that we don’t understand in our work. They are a complete problem-solving framework and that is what we need to output.

It is important to highlight that ADR also records the consequences of decisions, which can be positive or negative. This part is crucial as it allows us to learn knowledge that can only be known after the problem occurs. It is an important component of safe-fail and knowledge management.

Summary

Making competent technical analysis is just the starting point. High-quality technical analysis is an important indicator of becoming a key role in a team and a crucial method to improve our thinking abilities. When we can come up with alternative solutions and approach problems from different perspectives, our capabilities are enhanced.

If we want to extend further, I would like to quote three sentences from the book The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness:

Between stimulus and response, there is a space.

In that space lies our freedom and power to choose our response.

In these choices lie our growth and our happiness.

Known-Unknown is the space between stimulus and response. If we can focus our problem-solving efforts in this space and conduct high-quality analysis, we will gain freedom, and our abilities and sense of happiness will continue to improve.

Comments