Recently, when discussing issues with my team, we often encounter unknown problems (problems that we either don’t know we know or don’t know we don’t know). The final conclusion is usually that we are powerless. Unless it actually occurs and we become aware of its existence, how can we possibly address something we don’t know? So, what should we do about such problems?

Unknown problems can be recognized

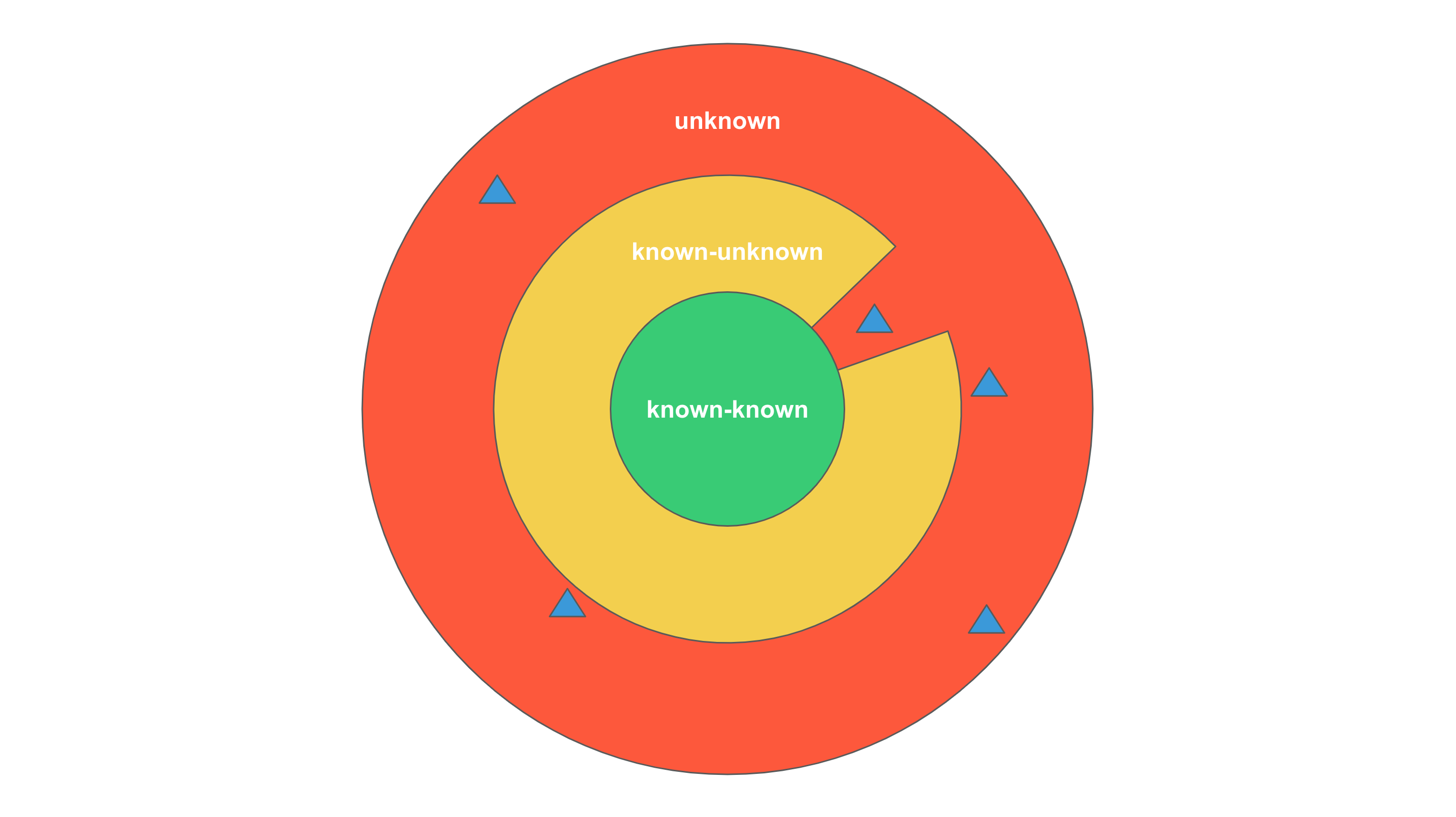

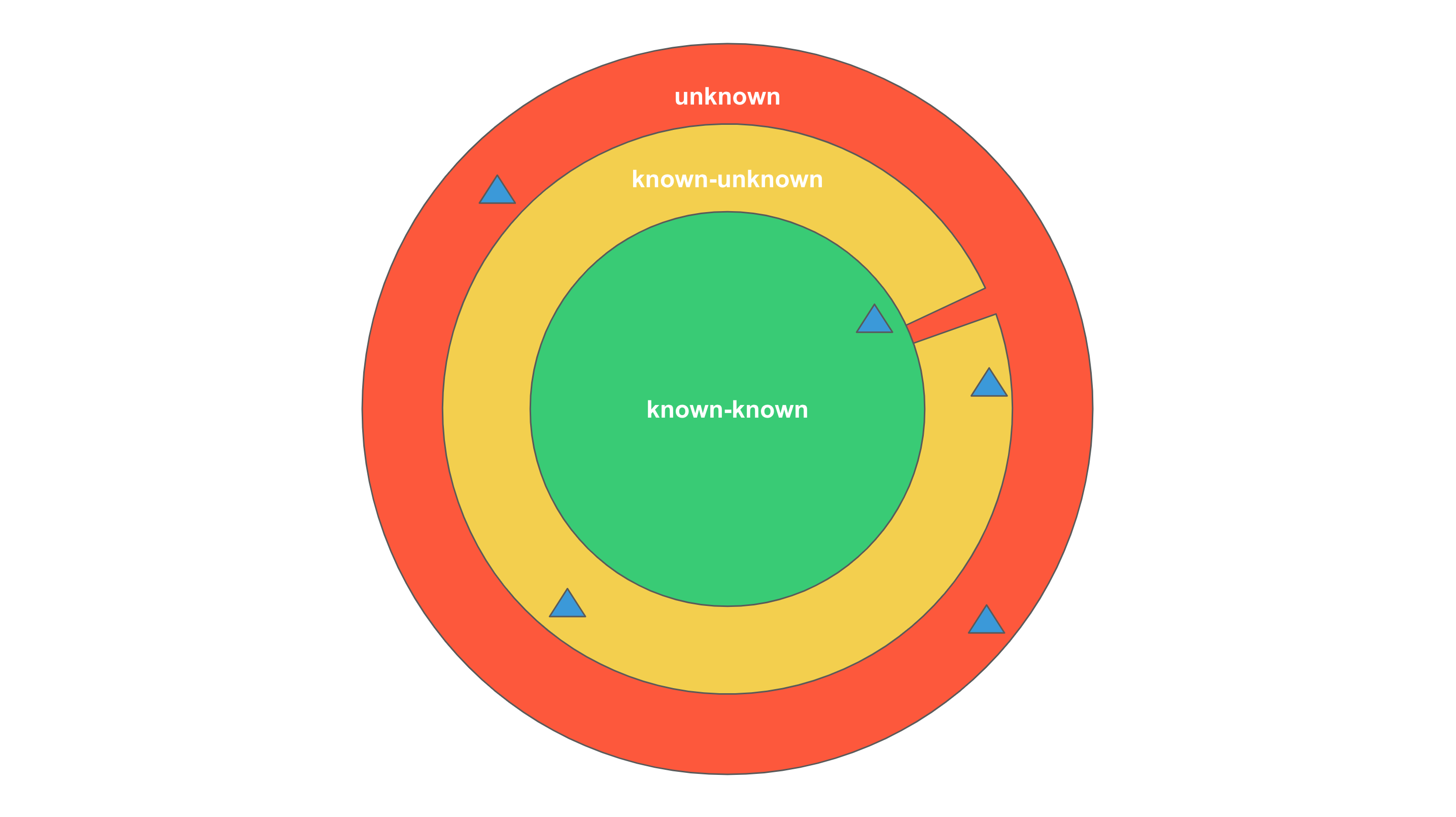

Our understanding of problems can be divided into three levels. The core level consists of problems we know we know. The middle level includes problems we know we don’t know. The outermost level comprises problems we are unaware of, which are the unknown problems.

When we encounter an unknown problem, we become aware of its existence. If we understand it, it becomes a problem we know we know, such as a compilation error. Before compilation, we are unaware of its existence, but once detected, anyone can understand and fix it based on the syntax. If we don’t understand it, it becomes a problem we know we don’t know, such as COVID-19. Before the outbreak, we were unaware of its existence. After its discovery, we neither understood its pathology nor could we create an effective vaccine, leaving it as something unexplained for experts to study.

Recognizing unknown problems comes at a cost

When facing unknown problems, we neither know what they are nor when they will occur, and we cannot guarantee that we will perceive them once they happen. Therefore, losses are almost inevitable.

For some problems, once they appear, we can quickly perceive them, accurately define them, and thus find solutions. For others, we cannot perceive them immediately; we only notice them when they become severe or occur frequently enough, prompting us to try to define them.

There are also problems that, although perceivable, cannot be accurately defined, forcing us to wait for them to recur so that we can collect enough data to define them. For example, in the early stages of COVID-19, it was mistaken for ordinary pneumonia until the number of cases increased and the situation worsened, leading people to realize it was a new disease and begin collecting more data to study its pathology and develop vaccines.

Thus, recognizing unknown problems is built upon unavoidable losses. Only when the losses are acceptable do we have the opportunity to perceive, define, and study them. Otherwise, we may be unable to continue related activities, making these problems meaningless to us. Take driving as an example: life safety is our bottom line. If lives are lost in car accidents, researching how to prevent issues like sudden lane changes, tire blowouts, or mudslides in future drives becomes meaningless to us.

How to handle unknown problems?

Minimize losses

We generally define a problem as the gap between the result achieved through effort (the current state) and the expected result (the goal). Although we may not know what the problem is, we usually have a clear definition of the goals and a clear understanding of the losses caused by not achieving them.

For example, we might not know why a system is malfunctioning, but we know that any system error can affect user experience and company revenue, and we can minimize these losses without knowing the system’s internal logic.

We can borrow concepts from the Project Management Triangle, reducing losses in three aspects: problem duration, impact scope, and functional investment.

-

Shorter problem duration means smaller losses

The shorter the duration of a problem, the smaller the loss. For example, in an earthquake, regardless of its magnitude or range, the shorter the duration, the smaller the loss. In software development, we can shorten problem discovery time through alert monitoring, reduce system rollback time using Feature Toggles, blue-green deployments, and disaster recovery, decrease problem localization time with good automated testing, and shorten problem resolution time with rapid CI/CD.

-

Smaller impact scope means smaller losses

The smaller the affected area, the smaller the loss. For instance, in a fire, a smaller burn area results in smaller losses. In software development, we can control the impact scope of a feature by using A/B testing or canary releases, thereby controlling the problem’s impact range.

-

Lower functional investment means smaller losses

Taking earthquakes again as an example, the smaller the population density, number of buildings, or economic scale in the seismic zone, the smaller the losses. In software development, we can reduce the number of features released each iteration to minimize losses from feature errors. We can further break down user stories to reduce the time and manpower invested in each story card, thereby minimizing losses from story card errors. Of course, this assumes that we do not build new features based on unvalidated ones. If this assumption is violated, we need to consider all unvalidated features as a whole, increasing losses if errors occur.

Establish feedback mechanism

Merely minimizing losses is not enough to handle unknown problems; we also need to establish a feedback mechanism to turn unknown problems into known ones. Even if we minimize losses, recurring problems can accumulate into significant losses. By turning unknown problems into known ones, we can learn from them and reduce the occurrence of similar issues.

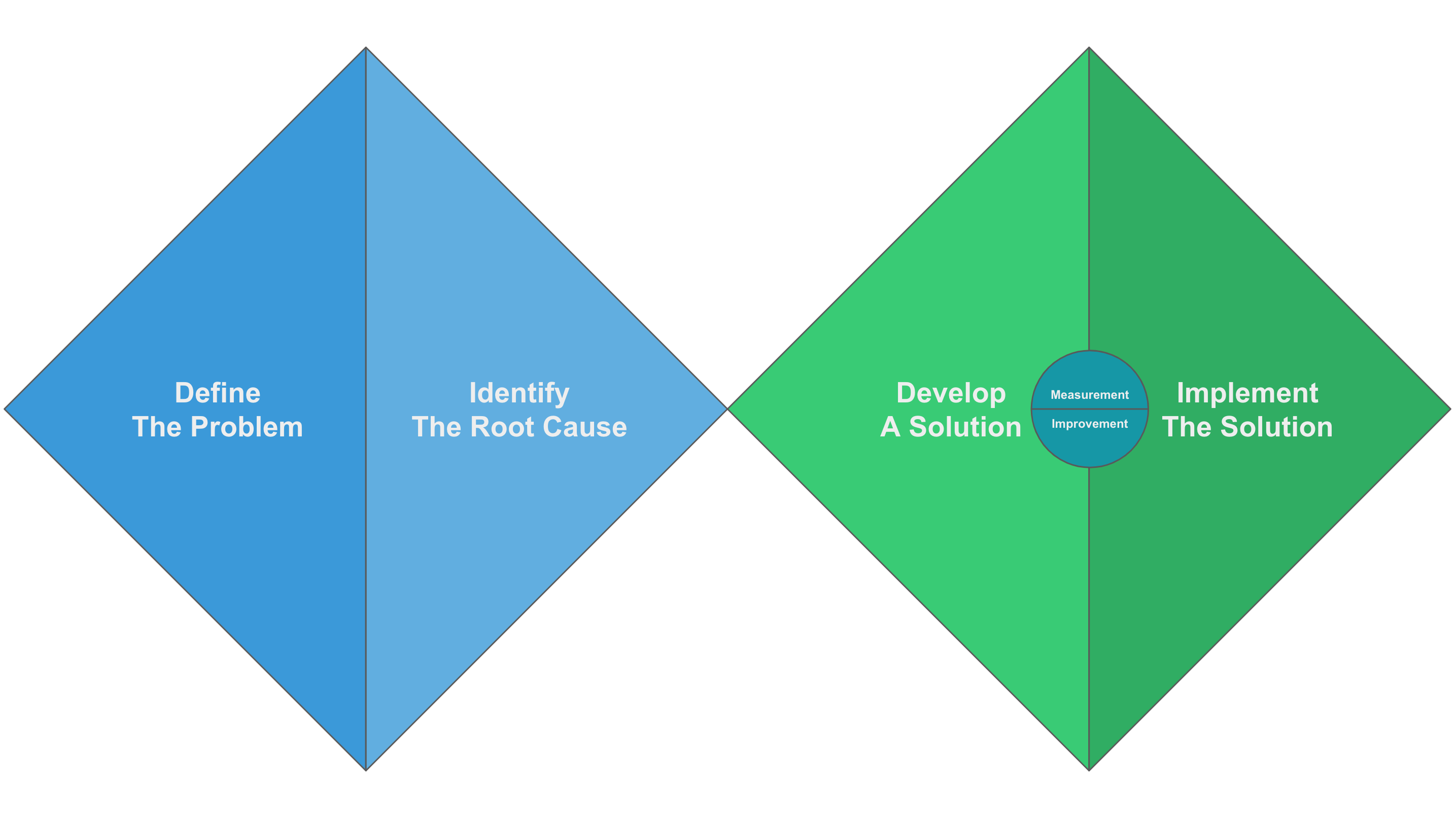

The first two steps of feedback mechanism are defining the problem and identifying the root cause, which I have detailed in How to perform a root cause analysis using ChatGPT? Here, I want to emphasize that the deeper the root cause we identify, the more potential problems we can prevent.

The third step is developing a solution, which I have thoroughly discussed in How to make a competent technical analysis? and How to do bug analysis? What I want to emphasize here is that the solutions must focus on optimizing processes and enhancing capabilities.

The fourth step is implementing the solution. This is the most critical step. Having a solution does not guarantee its implementation; I have seen too many solutions end up unresolved. The reasons vary: some solutions are impractical, some are not focused enough, the team is overwhelmed, and some solutions are not assigned to individuals. The key here is that we need to measure the implementation of the solution and promptly improve it.

In software development, Iteration Retrospective Meetings and Post-Incident Reviews (PIR) are the most common feedback mechanisms. However, they focus on the first three steps of the feedback process. Teams need to establish corresponding mechanisms to ensure the implementation, measurement, and improvement of solutions. This way, we can continuously convert unknown problems into known ones, forming a virtuous cycle of continuous learning and improvement.

Conclusion

Acknowledging the existence of unknown problems does not mean we can neglect efforts to prevent them. On the contrary, we need to make every effort to avoid problems and achieve Zero Defects. Only under the premise of zero defects does it make sense to handle unknown problems by minimizing losses and establishing feedback mechanisms. Otherwise, we won’t be able to distinguish between unknown and known problems.

Therefore, tactically, we must ensure zero defects. Strategically, we must acknowledge the existence of unknown problems, cultivate the ability to learn from them, minimize the losses they cause, and establish feedback mechanisms. This way, we can effectively handle unknown problems.

Comments